Key takeaways

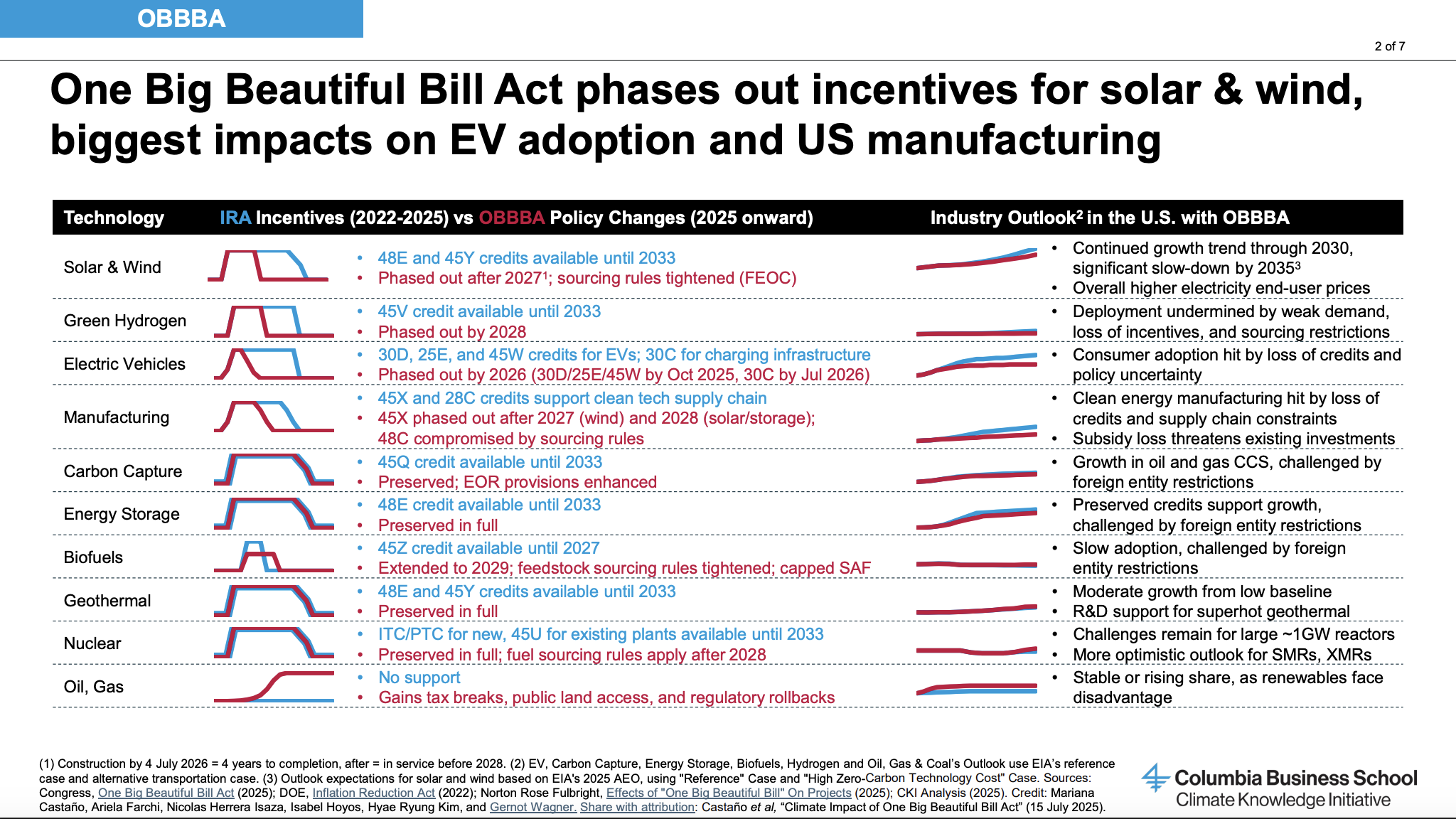

- The OBBBA reverses much of the IRA’s long-term stability. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act shortens tax credit timelines and tightens qualification rules, undermining the clear investment pathway created by the Inflation Reduction Act.

- Two big uncertainties remain, likely to slow down investment. Narrower “safe harbor” definitions and stricter Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC) rules, still to be announced by the Treasury, could block certain projects from qualifying for tax credits, delaying or freezing them .

- The impacts of the OBBBA will vary across technologies. Solar, wind, EVs, and efficiency upgrades will see a short-term rush before incentives expire, while firm power technologies like nuclear, geothermal, and storage retain longer-term support to keep costs falling.

- Resilient growth drivers will keep pushing the transition forward. State policies, domestic manufacturing , rising electricity demand from electrification, corporate clean energy commitments, and utility-led efficiency initiatives will keep the U.S. clean energy transition moving forward, though at a slower pace than under the IRA. OBBBA doesn't stop America's energy transition, and the policy incentives today are still much stronger than they were prior to the introduction of the IRA.

What happened and what’s at stake?

When the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed in 2022, it gave clean energy technologies a clear pathway for growth and investment, with tax credits stretching out to 2033 and beyond. The legislation created unprecedented momentum for climate technologies, spurring billions in private investment and positioning the United States as a global leader in the clean energy transition.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law by Trump in July this year, alters this trajectory. It compresses the tax credit timelines for some technologies, introduces new hurdles for getting the credits, and creates uncertainty for developers and investors who had been planning projects based on the IRA's stable, long-term incentive structure.

The Two Big Uncertainties

After eight months of “wait-and-see,” one might hope the market has at least a defined policy landscape and a clear, reshaped playing field. But the devil’s in the details and uncertainties remain in important areas for project financing.

Safe harbor definitions & permitting bottleneck

The OBBBA gives wind and solar projects until July 2026 to commence construction. Today’s uncertainty largely stems from how the federal government will determine whether a project has commenced construction in time. Developers have historically relied on a well-understood Treasury Department framework for proving that construction has started on a particular project: Either by spending at least 5% of project costs, or by beginning physical work. Meeting either threshold secures a “safe harbor” period, currently four years, for the developer to complete the project and place it in service.

But Trump’s July 7 executive order instructs the Treasury to narrow safe harbor definitions, potentially making it harder for projects to qualify for tax credits. Combined with Trump’s pledge to make permitting for wind and solar projects more difficult, developers now face a race against time to begin construction before the new restrictions take effect.

FOEC complications

China dominates supply chains for critical minerals, batteries, and clean energy technology. The Biden administration designed Foreign Entity of Concern rules (FEOC - Iran, North Korea, Russia, China) to reduce this dependence, build resilience, and ensure U.S. and allied manufacturing capture economic benefits. The original FEOC framework aimed for gradual "de-risking" from Chinese supply chains (not total decoupling) while cooperating with allies like Australia, Japan, and G7 partners for critical minerals. Biden's design was measured: focused on EVs, batteries, and critical minerals, with phased rules giving companies time to adjust.

After December 2025, stricter rules for FEOC will apply for tax credit eligibility. And just like the new safe harbor definitions, they may prove difficult to meet for certain technologies.

For clean electricity projects starting construction next year, 40% of the value of the materials used must be free of ties to a FEOC. By 2030, that threshold rises to 60%. Energy storage facilities are subject to a more aggressive timeline and would be required to prove that 55% of project materials are non-FEOC by 2026, rising to 75% by 2030. Each covered advanced manufacturing technology has its own FEOC benchmarks. Tax experts warn these rules may be difficult to comply with

The details of how this will work will also depend heavily on guidance from the Treasury Department. This gives the Trump administration significant discretion over the rules. With Treasury now understaffed and having until end of 2026 to provide guidance, developers still face policy risk and investors might become more cautious.

The result of these uncertainties?

Ultimately, hundreds of billions of dollars in planned clean-energy investments might remain frozen while companies wait for the details to take shape.

But rather than retreat, we see investors adapting to the new landscape. Assets and company values might temporarily dip below fundamentals due to market hesitation, creating attractive entry points for disciplined capital deployment. The clean energy sector’s fundamentals remain strong to support continued growth, just with more selective capital allocation.

How will these changes play out across different technologies?

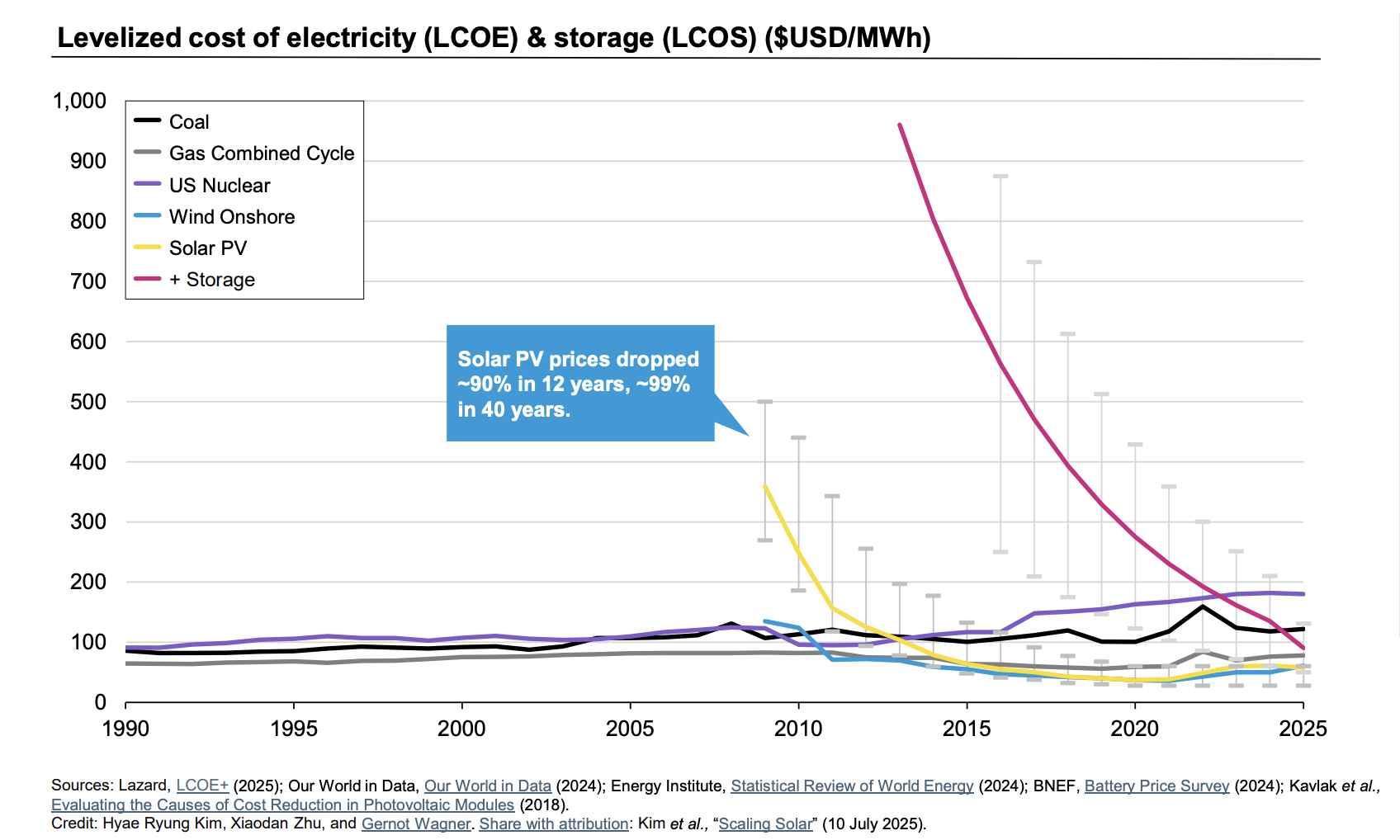

Solar and Wind: short-term rush, long-term growth continues

For solar and wind, the shorter window means developers will be rushing to begin projects. Over the next year, we are likely to see a surge in buildouts and safe-harbouring as developers work to secure credits. After that, the pace of new projects may slow but will not stop. Renewables remain the most cost-competitive and fastest source of new power generation.

One major driver keeping momentum strong is the rapid growth of data centers, which require large amounts of electricity as soon as possible. In many states, renewables are still the quickest way to meet this demand, especially given the shortage of gas turbines, which now have lead times exceeding five years. Tech companies such as Meta are building data centers powered by massive solar plants, while companies like Crusoe are using a mix of renewables and second-life electric vehicle batteries to power facilities. In short, there will not be a collapse in development, because the demand for renewables is still strong. This matters because rapidly deploying solar, and wind and batteries is still the best way to cut emissions in the near term.

EVs and energy-efficient homes: another short-term rush and then state-level support?

Tax credits for electric vehicles and energy efficiency upgrades in buildings are also ending much sooner under the OBBBA than under the IRA. Just like for wind and solar project this will likely create a purchase surge followed by a slowdown once the credits expire. EVs will likely continue to grow, driven by their financial appeal. Even without tax credits 37% of new cars bought in 2030 are expected to be electric, that's down from the 48% projected under the IRA but still much higher than the roughly 10% it is today.

Energy efficiency will lose tax credits quickly, though states and utilities are stepping in to help fill the gap. For example, California and New York still offer up to $8,000 for heat pumps, and Massachusetts is running a pilot program that gives heat pump owners a big discount on winter electricity bills.

Firm power and storage: will keep moving down the cost curve

On a brighter note, other sources of zero-emission electricity, which still play a limited role in the energy mix today, such as advanced nuclear, fusion, geothermal, and also battery storage, will be able to claim tax credits for nearly a decade. Grid upgrades also remain a focus for the Department of Energy. This is important because these technologies are more expensive than wind or solar and need stable policy support to become cheaper and more widely available. The impact of the new Foreign Entities of Concern rules is still uncertain for these technologies but the fact that their credits are staying in place is an important signal.

The silver lining: resilient growth in a new era

Still, key drivers for climate technology adoption in the United States will keep pushing the transition forward.

- State-level support continues to be a major force (remember that California alone represents the world’s fourth-largest economy).

- The focus on reshoring manufacturing and building resilient supply chains is benefiting US manufacturers of critical technologies, such as grid transformers and batteries.

- Electrification is driving rapid growth in electricity demand, meaning the need for smart grid and energy technologies is still on the rise.

- Major technology companies like Microsoft and Google are investing heavily in datacenter infrastructure powered by clean energy and cooled with energy-efficient technologies. In 2025 alone, Microsoft plans to spend $80 billion on AI data centers, and Google will spend $85B. These massive capex investments are presenting key opportunities for climate technologies, with access to energy currently being the biggest constraint for these companies.

- Utilities, recognizing the value of energy efficiency and virtual power plants, are looking for ways to relieve the constraints on the grid to minimise expensive investments in grid transmission and distribution.

Together with a robust innovation ecosystem and abundant growth capital, these factors position the United States’ energy transition to continue making progress. Although the framework for clean energy has become more fragmented, it remains stronger than it was before the Inflation Reduction Act, with several important provisions still intact. Many of the technologies most affected by the OBBBA, including solar, wind, electric vehicles and heat pumps, are already competitive in the marketplace without subsidies. And while the OBBBA undoubtedly introduces new constraints, it also clarifies the opportunities and strengthens long-term trends toward domestic manufacturing and supply chain resilience.